File I/O & Durability - Why fsync() Is Your Best Friend (And Worst Enemy)

Series: Backend Engineering Mastery

Reading Time: 13 minutes

Level: Junior to Senior Engineers

The One Thing to Remember

fsync() is your durability guarantee. Without it, your "written" data might just be sitting in kernel buffers, vulnerable to power loss. With it, you trade performance for safety.

But here's the scary part: Ever had write() return success, only to lose data on a power outage? That's because write() lies—it returns when data is in memory, not on disk.

Building on Article 2

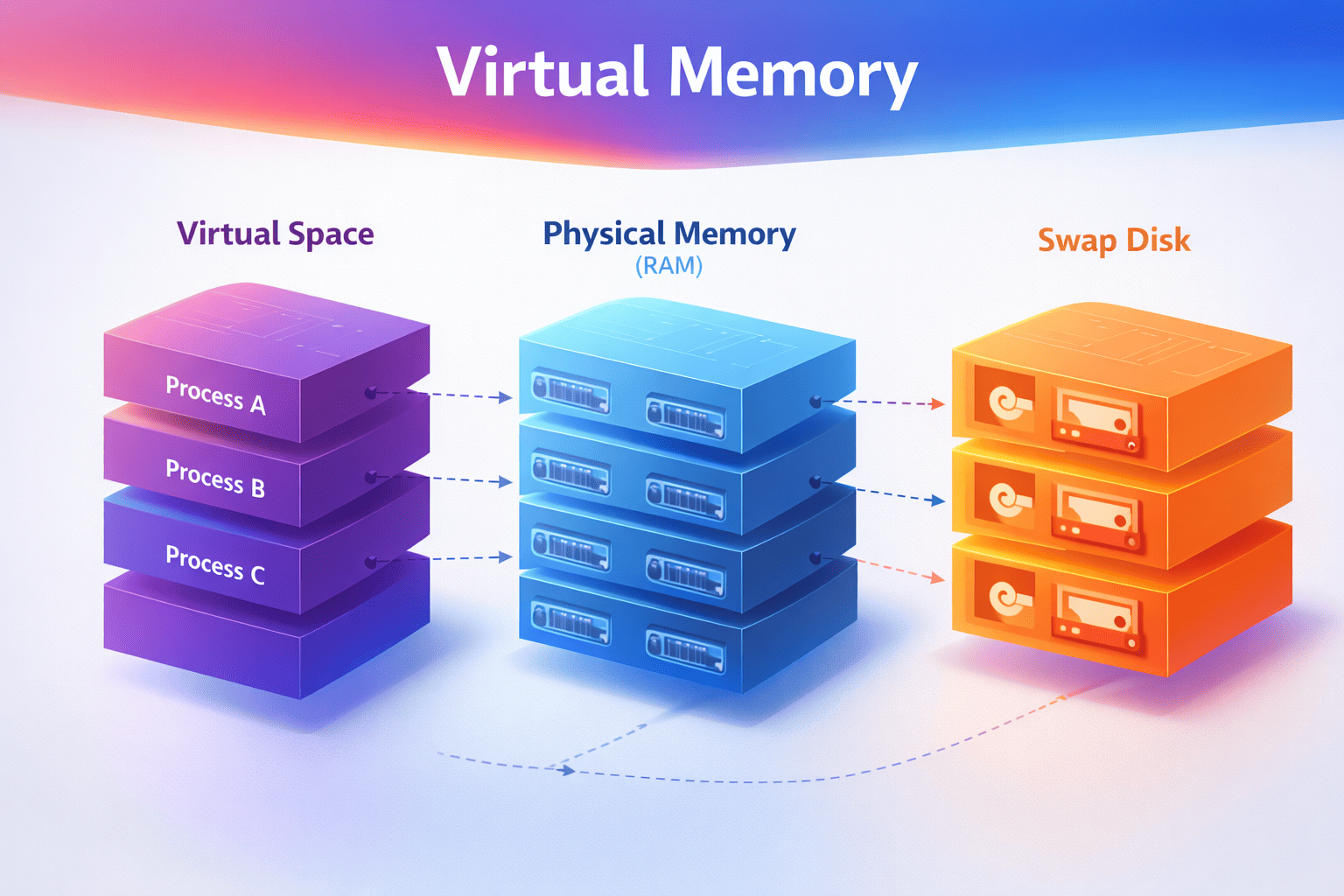

In Article 2: Memory Management, you learned about the page cache—that's where your data goes when you call write(). But here's the critical question: How does data actually get from that page cache to disk?

The journey from your application's memory to physical storage is full of trade-offs. Understanding this path is the difference between losing hours of data and having true durability.

← Previous: Article 2 - Memory Management

Why This Matters

I've seen:

- A startup lose 2 hours of user data after a power outage because they didn't understand write durability

- A database migration fail silently because rename() wasn't followed by fsync()

- An engineer spend 3 days debugging "data corruption" that was actually incomplete writes

- An AI training job lose checkpoint data because the model weights weren't synced to disk

This isn't academic knowledge—it's the difference between:

-

Losing data vs keeping it safe

- Understanding fsync() = you know when data is truly durable

- Not understanding = you think data is safe, but it's not

-

Debugging in hours vs days

- Knowing the write path = you immediately check fsync() calls

- Not knowing = you blame the database, the network, everything except the actual problem

-

Choosing the right durability strategy

- Understanding trade-offs = you pick fsync frequency that matches your needs

- Not understanding = you either lose data or kill performance

Understanding the write path is the difference between "I think the data is saved" and "I know the data is saved."

Quick Win: Check Your Write Durability

Before we dive deeper, let's see if your system is actually syncing data:

# See how much data is waiting to be written (dirty pages)

cat /proc/meminfo | grep -E "Dirty|Writeback"

# Watch dirty pages in real-time during writes

watch -n 1 'cat /proc/meminfo | grep Dirty'

# Check if a process is calling fsync()

strace -e fsync,fdatasync -p $(pgrep your-app | head -1)

What to look for:

- High Dirty pages: Lots of data waiting to be written (potential data loss risk)

- No fsync() calls: Your app might not be syncing (data loss on crash!)

- Frequent fsync(): Good for durability, but might be slow

The Write Path: From App to Disk

When you call write(), your data takes a long journey:

APPLICATION KERNEL HARDWARE

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ Application │ │ Page Cache │ │ Disk │

│ Buffer │ │ (RAM) │ │ (Persistent) │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ "Hello World" │───────►│ "Hello World" │───────────►│ "Hello World" │

│ │ write()│ │ Later │ │

│ │ │ │ (maybe) │ │

└─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘

│ │

│ │

[ VULNERABLE ] [ DURABLE ]

Power loss here Power loss here

= data LOST = data SAFE

The Four Stages of a Write

| Stage | Location | Speed | Durability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. App buffer | Your process memory | Instant | Lost on crash |

| 2. Page cache | Kernel memory | Fast (~μs) | Lost on power loss |

| 3. Disk cache | Drive's own RAM | N/A | Lost on power loss* |

| 4. Disk platters/cells | Physical storage | Slow (~ms) | Durable |

*Enterprise SSDs with capacitors can flush their cache on power loss

Quick Jargon Buster

- Page Cache: Kernel's memory buffer for file data (from Article 2!)

- fsync(): System call that forces data from page cache to disk

- fdatasync(): Like fsync() but only syncs data, not metadata (faster)

- O_DIRECT: Flag to bypass page cache entirely (advanced, used by databases)

- Dirty Pages: Modified pages in cache that haven't been written to disk yet

- Write-Ahead Log (WAL): Write operations to log first, then apply (databases use this)

Visual: Write Modes Compared

BUFFERED WRITE (Default - DANGEROUS for important data):

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

App ──► write() ──► Page Cache ──► [sometime later...] ──► Disk

│

└──► write() returns SUCCESS immediately!

Timeline:

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────►

│ │ │

write() Returns Actually on disk

called "success" (30 sec later??)

⚠️ Power loss between write() and disk sync = DATA LOST

WRITE + FSYNC (SAFE):

════════════════════

App ──► write() ──► Page Cache ──► fsync() ──► Disk ──► Returns

│

│

Timeline: │

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────► │

│ │ │ │

write() In page cache fsync() Success!

called waits for disk Data is safe

✅ When fsync() returns, data is on physical storage

O_DIRECT (Bypass page cache - SPECIALIZED):

═══════════════════════════════════════════

App ──► write() ──────────────────────────────────► Disk ──► Returns

- Bypasses page cache entirely

- App must handle its own buffering

- Used by databases that know better than the OS

✅ Control over when data hits disk

⚠️ No OS-level caching benefits

Trade-offs: The Durability-Performance Spectrum

The Fundamental Trade-off

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ DURABILITY ◄───────────────────────► PERFORMANCE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ fsync every fsync every fsync on No fsync │

│ write second close only (buffered) │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌───────┐ ┌───────┐ ┌───────┐ ┌───────┐ │

│ │~1,000 │ │~50,000│ │~200,000│ │~500,000│ │

│ │writes │ │writes │ │writes │ │writes │ │

│ │/sec │ │/sec │ │/sec │ │/sec │ │

│ └───────┘ └───────┘ └───────┘ └───────┘ │

│ │

│ Zero data loss Lose ~1 sec Lose data since Lose all │

│ on power loss on power loss last close buffered data│

│ │

│ Use: Databases, Use: Logs, Use: Temp files, Use: Caches, │

│ Financial txns important data build artifacts scratch data │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Redis Persistence Modes: A Perfect Case Study

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ REDIS AOF PERSISTENCE OPTIONS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ appendfsync always appendfsync everysec appendfsync no│

│ ───────────────── ───────────────────── ──────────────│

│ │

│ fsync() after EVERY fsync() once per fsync() never │

│ write command second (OS decides) │

│ │

│ Performance: ~1K ops/s Performance: ~100K/s Performance: Max│

│ Data loss: None Data loss: ~1 second Data loss: 30s+│

│ │

│ Use for: Use for: Use for: │

│ - Financial data - Most use cases - Pure cache │

│ - Can't lose anything - Good balance - Replaceable │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Code Examples

Unsafe vs Safe Write

import os

import time

def unsafe_write(filename, data):

"""

Data might be lost on power failure!

write() returns when data is in page cache, NOT on disk.

"""

with open(filename, 'w') as f:

f.write(data)

# File closed, but data might still be in kernel buffers!

def safe_write(filename, data):

"""

Data survives power failure.

"""

with open(filename, 'w') as f:

f.write(data)

f.flush() # Flush Python's internal buffer to OS

os.fsync(f.fileno()) # Flush OS buffer to disk

# IMPORTANT: Also sync the directory for the file metadata!

dir_fd = os.open(os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(filename)), os.O_RDONLY)

os.fsync(dir_fd)

os.close(dir_fd)

# Benchmark the difference

data = "x" * 10000 # 10KB

start = time.time()

for i in range(100):

unsafe_write(f'/tmp/unsafe_{i}.txt', data)

print(f"Unsafe writes: {time.time() - start:.3f}s")

start = time.time()

for i in range(100):

safe_write(f'/tmp/safe_{i}.txt', data)

print(f"Safe writes: {time.time() - start:.3f}s")

# Typical output:

# Unsafe writes: 0.015s

# Safe writes: 1.500s (100x slower!)

The Atomic Write Pattern (Gold Standard)

import os

import tempfile

def atomic_write(filepath, data):

"""

The safest write pattern:

1. Write to temp file

2. fsync temp file

3. Rename (atomic on POSIX)

4. fsync directory

At no point is the file in a partially-written state!

"""

directory = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(filepath))

# Create temp file in same directory (important for rename!)

fd, tmp_path = tempfile.mkstemp(dir=directory)

try:

# Write data to temp file

os.write(fd, data.encode() if isinstance(data, str) else data)

# Ensure data is on disk

os.fsync(fd)

os.close(fd)

# Atomic rename - either completes fully or not at all

os.rename(tmp_path, filepath)

# Sync directory to persist the rename

dir_fd = os.open(directory, os.O_RDONLY)

os.fsync(dir_fd)

os.close(dir_fd)

except:

# Clean up temp file on error

os.close(fd)

os.unlink(tmp_path)

raise

# Usage

atomic_write('/tmp/important.txt', 'critical data')

# Even if power fails during this:

# - Old file is intact, OR

# - New file is complete

# NEVER a partially-written file!

Database-Style Write-Ahead Logging

import os

import json

import time

class WriteAheadLog:

"""

Simple WAL implementation demonstrating durability pattern.

Sequence:

1. Write operation to log file (with fsync)

2. Apply operation to main data

3. Periodically checkpoint (consolidate log)

"""

def __init__(self, data_file, log_file):

self.data_file = data_file

self.log_file = log_file

self.data = self._load_data()

self._replay_log()

def _load_data(self):

try:

with open(self.data_file, 'r') as f:

return json.load(f)

except FileNotFoundError:

return {}

def _replay_log(self):

"""Replay any operations from log after crash"""

try:

with open(self.log_file, 'r') as f:

for line in f:

op = json.loads(line)

self._apply_op(op, log=False)

except FileNotFoundError:

pass

def _apply_op(self, op, log=True):

if log:

# FIRST: Log the operation (durable)

with open(self.log_file, 'a') as f:

f.write(json.dumps(op) + '\n')

f.flush()

os.fsync(f.fileno())

# THEN: Apply to in-memory state

if op['type'] == 'set':

self.data[op['key']] = op['value']

elif op['type'] == 'delete':

self.data.pop(op['key'], None)

def set(self, key, value):

self._apply_op({'type': 'set', 'key': key, 'value': value})

def get(self, key):

return self.data.get(key)

def checkpoint(self):

"""Write full state to data file, clear log"""

# Write new data file atomically

atomic_write(self.data_file, json.dumps(self.data))

# Clear log

with open(self.log_file, 'w') as f:

os.fsync(f.fileno())

# Usage

wal = WriteAheadLog('/tmp/data.json', '/tmp/wal.log')

wal.set('user:1', {'name': 'Alice', 'balance': 100})

# Even if crash here, data is safe in WAL

Real-World Trade-off Stories

PostgreSQL's fsync() Disaster (2018)

Situation: PostgreSQL called fsync() on files, but some Linux kernels had a bug where fsync() errors weren't properly reported.

What happened:

- Kernel buffer writeback failed

- fsync() returned success (bug!)

- PostgreSQL thought data was safe

- Data was actually lost

The fix: PostgreSQL now retries writes on fsync failure and has added extensive error checking.

Lesson: Even "safe" operations can have edge cases. Defense in depth matters.

Spotify's Write Amplification

Situation: Spotify was syncing user state to disk very frequently for durability.

Problem:

- Each small write triggered a full 4KB page write

- Many small writes = many 4KB writes = "write amplification"

- SSDs were wearing out prematurely

Solution:

- Batch small writes into larger ones

- Use a write-ahead log pattern

- Checkpoint periodically instead of syncing every change

Lesson: fsync() is expensive. Batch operations when possible.

MongoDB's Controversial Default

Situation: Early MongoDB defaulted to unacknowledged writes.

What users expected: "Write complete" = data is safe

What actually happened: "Write complete" = data is in memory

Result: Multiple companies lost data during crashes.

MongoDB's response: Added write concern options, changed defaults.

// Old dangerous default

db.users.insert({name: "Alice"}) // Returns before durable!

// New safer approach

db.users.insert({name: "Alice"}, {writeConcern: {w: 1, j: true}})

// w: 1 = acknowledged by primary

// j: true = journaled (fsync'd)

Lesson: Understand your database's durability guarantees. Don't assume.

AI Model Checkpointing: Durability vs Training Speed

Situation: Training a large ML model for hours, need to checkpoint periodically. Power outage could lose days of work.

The problem:

- Model weights are large (GBs)

- fsync() is slow (100-500μs per sync)

- Checkpointing too often slows training

- Checkpointing too rarely risks losing work

Solution pattern:

def checkpoint_model(model, checkpoint_path):

"""Atomic checkpoint write for ML models"""

# 1. Write to temp file (same directory for atomic rename)

tmp_path = checkpoint_path + '.tmp'

# 2. Save model to temp file

torch.save(model.state_dict(), tmp_path)

# 3. Sync to disk (critical!)

import os

fd = os.open(tmp_path, os.O_RDONLY)

os.fsync(fd)

os.close(fd)

# 4. Atomic rename

os.rename(tmp_path, checkpoint_path)

# 5. Sync directory (for metadata)

dir_fd = os.open(os.path.dirname(checkpoint_path), os.O_RDONLY)

os.fsync(dir_fd)

os.close(dir_fd)

Trade-off:

- Checkpoint every N epochs: Balance between safety and speed

- Use async checkpointing: Save in background thread (but still fsync!)

- Compress checkpoints: Smaller files = faster fsync()

Lesson: For long-running AI training jobs, checkpoint durability is critical. Use atomic writes and verify with actual power-off tests.

Debugging I/O Issues

See Dirty Pages (Unflushed Data)

# How much data is waiting to be written to disk?

cat /proc/meminfo | grep -E "Dirty|Writeback"

Dirty: 12345 kB # Data modified, not yet written

Writeback: 0 kB # Data currently being written

# High Dirty = lots of buffered writes

# Watch it during your application's writes

watch -n 1 'cat /proc/meminfo | grep Dirty'

Monitor Disk I/O

# Real-time I/O statistics

iostat -x 1

Device r/s w/s await %util

sda 100 500 2.5 45%

# Key metrics:

# w/s = writes per second

# await = average wait time (ms) - should be < 10ms for SSD

# %util = how busy the disk is - 100% = saturated

Trace System Calls

# See what a process is writing

strace -e write,fsync,fdatasync -p <PID>

# Example output:

write(3, "data here...", 100) = 100

fsync(3) = 0 # <-- This is where durability happens!

Check Filesystem Mount Options

# See how your filesystem is mounted

mount | grep "on / "

# Look for:

# data=ordered - metadata journaled, data written before metadata (default)

# data=journal - both journaled (safest, slowest)

# data=writeback - fastest, least safe

# For ext4, check:

tune2fs -l /dev/sda1 | grep "Default mount"

Common Confusions (Cleared Up)

"write() returns, so data is on disk!"

Reality: write() returns when data is in the page cache (kernel memory), not on disk. It might be written later, or it might be lost on power failure.

"close() flushes data to disk!"

Reality: close() flushes your application's buffer to the OS page cache, but doesn't sync to disk. You still need fsync() for durability.

"rename() is atomic, so I'm safe!"

Reality: rename() is atomic for the operation, but you still need to:

- fsync() the file contents before rename

- fsync() the directory after rename

Otherwise, the rename might complete but the file contents could be lost.

"My database handles this, I don't need to worry!"

Reality: Database defaults vary. Many default to performance over durability. Always check your database's durability settings and test with actual power loss.

Common Mistakes

Mistake #1: "Closing a file flushes it to disk"

Why it's wrong: close() flushes Python/C buffers to OS, not OS buffers to disk.

# WRONG - Not durable!

with open('file.txt', 'w') as f:

f.write('important data')

# File closed, but data may still be in page cache!

# RIGHT - Durable

with open('file.txt', 'w') as f:

f.write('important data')

f.flush()

os.fsync(f.fileno())

Mistake #2: "rename() is atomic, so I don't need fsync"

Why it's wrong: rename() is atomic for the operation itself, but both the file contents AND the directory entry need to be synced.

# WRONG - rename without syncing

with open('file.tmp', 'w') as f:

f.write(data)

os.rename('file.tmp', 'file.txt') # Might lose everything!

# RIGHT - sync everything

with open('file.tmp', 'w') as f:

f.write(data)

f.flush()

os.fsync(f.fileno())

os.rename('file.tmp', 'file.txt')

dir_fd = os.open('.', os.O_RDONLY)

os.fsync(dir_fd) # Sync directory!

os.close(dir_fd)

Mistake #3: "My database handles durability, I don't need to worry"

Why it's wrong: Default settings vary. Many databases default to performance over durability.

Check your settings:

-- PostgreSQL

SHOW fsync; -- Should be 'on'

SHOW synchronous_commit; -- 'on' for full durability

-- MySQL

SHOW VARIABLES LIKE 'innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit';

-- 1 = safest, 2 = flush once per second, 0 = no flush

Decision Framework

□ Is this data replaceable?

→ Yes: Buffered writes are fine

→ No: Need fsync

□ What's the acceptable data loss window?

→ 0 seconds: fsync every write

→ 1 second: fsync every second (batch)

→ 30 seconds: OS default

→ Don't care: Pure buffer

□ What's my write throughput requirement?

→ < 1,000/sec: fsync every write is fine

→ 1,000-100,000/sec: Batch writes, fsync periodically

→ > 100,000/sec: Consider async durability, accept some loss

□ Is this a database?

→ Always enable WAL/journaling

→ Check your durability settings

→ Test with actual power-off!

Performance Numbers to Know

| Operation | Typical Latency | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| write() to page cache | ~1 μs | Just memory copy |

| fsync() to SSD | ~100-500 μs | Actual I/O |

| fsync() to HDD | ~5-15 ms | Mechanical seek |

| O_DIRECT write to SSD | ~50-100 μs | Bypass cache |

Rule of thumb: fsync() is 100-1000x slower than buffered write.

Memory Trick

"WASD" for write durability:

- Write: Puts data in kernel buffer (not safe!)

- All the way: fsync() gets it to disk

- Sync directory: Don't forget metadata

- Double-check: Verify with your specific hardware

Self-Assessment

Before moving on:

- [ ] Can you explain what happens between write() returning and data being on disk?

- [ ] Know when O_DIRECT is beneficial vs harmful?

- [ ] Could you implement an atomic file write that survives crashes?

- [ ] Understand why rename() alone isn't enough for durability?

- [ ] Know your database's default durability settings?

- [ ] Understand why close() doesn't guarantee durability?

- [ ] Know when to use atomic write patterns for AI model checkpoints?

Key Takeaways

- write() lies: Returns success when data is in kernel buffer, not on disk

- fsync() is truth: Only guarantee of durability, but expensive

- Atomic writes: temp file + fsync + rename + fsync directory

- Batch for performance: fsync once per second, not per write

- Verify your database: Check durability settings, test with actual power loss

What's Next

Now that you understand how data flows from memory to disk, the next question is: How does the OS actually schedule all these operations?

In the next article, Article 4: CPU Scheduling & Context Switches, you'll learn:

- How the OS decides which process runs when

- Why context switches matter for performance

- The trade-offs between throughput and latency

- How to measure and optimize scheduling overhead

This connects directly to what you learned here—when fsync() blocks waiting for disk I/O, the OS switches to another process. Understanding scheduling helps you understand why your app might be slow even when CPU isn't busy.

→ Continue to Article 4: CPU Scheduling & Context Switches

This article is part of the Backend Engineering Mastery series. Understanding I/O is fundamental to building reliable systems. You learned about memory management in Article 2, and now you understand how data flows from that memory to disk.